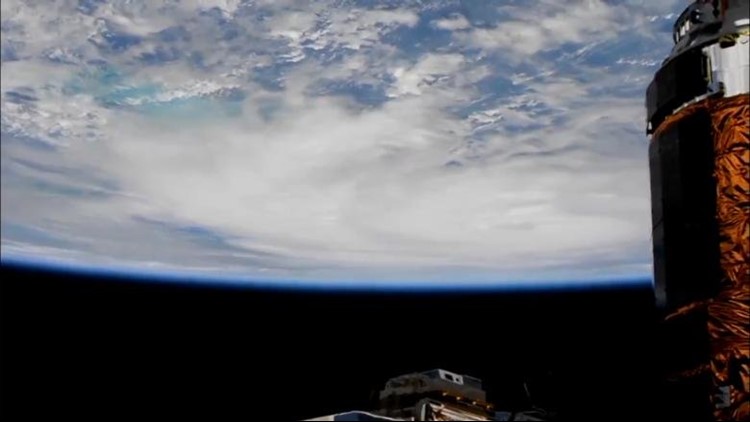

A potentially catastrophic Category 4 Hurricane Michael has made landfall in the Florida Panhandle with sustained winds of 155 mph, making this the strongest storm to hit the continental US since Hurricane Andrew smashed into South Florida in 1992.

The extremely dangerous center of Michael — also the strongest hurricane to hit the Florida Panhandle in recorded history — crossed near Florida’s Mexico Beach on Wednesday afternoon, the National Hurricane Center said. Its winds and storm surge wreaked havoc along the shore.

“I am scared to death for the people who chose not to evacuate. This is just a horrendous storm,” Gov. Rick Scott told CNN shortly after Michael’s landfall.

Streets were flooding in the Panhandle city of Apalachicola. In Panama City Beach, winds of about 100 mph furiously whipped the trees in the early afternoon as siding ripped from a building got caught against a fence.

Earlier in that oceanside city, video from a meteorologist showed new construction collapsing in high winds.

Among the concerns: Flash-flooding with heavy rain; life-threatening storm surges up to 14 feet high; and devastating winds, not just in the Panhandle, but southern Alabama and Georgia.

Michael’s wind could be dangerously strong well after landfall, into the night.

“That’s going to knock down a lot of trees, say, in the Tallahassee area, all of these areas inland. It’s going to be big problems … as far as the wind goes, and then coastal storm surge,” CNN meteorologist Jennifer Gray said.

Key developments

• As of shortly before 2 p.m. ET, Michael’s center had maximum sustained winds of 155 mph, moving inland near Mexico Beach.

• About 4.2 million people were under hurricane warnings in Florida’s Panhandle and Big Bend regions, along with parts of southeastern Alabama and southern Georgia. Tropical storm warnings cover 21 million people in several states.

• A wind gust of 130 mph was reported near Florida’s Tyndall Air Force Base, close to Panama City, before the instrument failed.

• Up to 14 feet of storm surge is expected in Apalachicola, likely this afternoon, near the peak of the storm. About 50% of residents there didn’t evacuate, Apalachicola Police Chief Bobby Varnes estimated. “If they need help, they can give a call, but it’s probably too dangerous. … There’s no ambulance service, no medical, so they’re pretty much going to be on their own until it lets up.”

• Michael still could be a Category 2 storm (wind speeds of 96-110 mph) when it crosses into southern Georgia on Wednesday evening, forecasters said. “The citizens in Georgia need to wake up and pay attention. … This is going to be the worst storm that southwest Georgia and central Georgia (has) seen in many, many decades,” Federal Emergency Management Agency Administrator Brock Long said.

• At least 103,000 customers are without power along the Florida Panhandle, utility companies said. “There will be hundreds of thousands, if not millions, without power for a very long time,” CNN meteorologist Chad Myers said.

Governor: ‘It’s too late to get on the road’

Gov. Scott on Monday and Tuesday urged people to get out of the way as Michael strengthened rapidly over the Gulf of Mexico after lashing Central America and western Cuba. Officials issued mandatory or voluntary evacuation orders in at least 22 counties on the Florida Gulf Coast.

Scott extended a state of emergency to 35 counties and activated 2,500 National Guardsmen; he said more than 1,000 search-and-rescue personnel will be deployed once the storm passes.

President Donald Trump approved a pre-landfall emergency declaration to provide federal money and help in Florida.

Before Michael, only three major hurricanes Category 3 or higher had struck the Panhandle since 1950: Eloise in 1975, Opal in 1995 and Dennis in 2005.

‘I’m definitely getting a little bit more scared’

Michael’s rapid intensification — it was a tropical storm in the Gulf on Sunday and a Category 1 hurricane midday Monday — may have caught some coastal residents by surprise, despite forecasters’ warnings of strengthening.

Newlyweds Jessica Ayers and Don Hogg told CNN they and some relatives were staying put in Panama City on Wednesday morning, having decided against leaving because they weren’t in an evacuation zone.

Michael’s intensification was unwelcome news.

“I’m definitely getting a little bit more scared, I have to say,” Ayers said.

They have a generator, so they hope to have power, should regular service stop. They’ve identified an interior bathroom as a place to take cover if winds get extreme.

Janelle Frost and Tracy Dunn told CNN they were staying put in nearby Panama City Beach. They said they wanted to stay to help those who couldn’t afford to leave, such as retirees.

“There’s so many people that live around where we’re at, and we wanted to make sure they’re OK,” Frost said. “We made the decision to stay to try and help them.”

In Tallahassee, Kaitlyn Mae Christensen Sacco said she was taking refuge in her home. She has a generator and a camp stove, and she parked her car at a nearby church lot bare of any trees that might come down.

“We have our bathroom set up with blankets, a battery-powered fan, water, snacks and the tub set up for our dogs with pee pads,” she said.

Even before landfall, Michael was sending ocean water onto the Panhandle’s shores. Water was creeping into the southern Wakulla County town of Panacea, a picture from the National Weather Service showed.

In Pensacola Beach huge waves were crashing ashore on Wednesday morning, video from Joe Durant showed.

Rain just one of several threats

A hurricane warning was in place from the Alabama-Florida border to the Suwannee River in Florida.

Meanwhile, tropical storm warnings were in effect for parts of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina. Storm surge warnings were in place along the Florida and Alabama coasts.

While Michael will weaken as it moves across the southeastern United States, its heavy rains and flooding effects will spread far and wide.

Up to 12 inches of rain could fall in Florida’s Panhandle and Big Bend areas, as well as southeastern Alabama and southern Georgia. Some parts of the Carolinas — recently deluged by Hurricane Florence — and southern Virginia could see up to 6 inches, the hurricane center said.

Florence made landfall last month as a Category 1 storm, killing dozens in the Carolinas and Virginia.

Michael’s rain and destructive winds aren’t its only serious threats.

Life-threatening storm surges could slam the Florida Gulf Coast, with the deadliest of possibly 9 to 14 feet expected near the eyewall and to the east — perhaps between Tyndall Air Force Base and the Aucilla River.

Damaging winds are expected in Florida, southeastern Alabama and southern Georgia. Tornadoes could spawn in the Southeast Wednesday into Thursday, forecasters said.

Emergencies in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina

Several airports in the Florida Panhandle closed because of the storm.

Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal declared an emergency for 108 counties.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey issued a statewide state of emergency, saying on Twitter it was “in anticipation of wide-spread power outages, wind damage and debris produced by high winds & heavy rain associated with Hurricane Michael.”

In South Carolina, Gov. Henry McMaster said an emergency declared for last month’s Hurricane Florence would be extended to cover effects from Hurricane Michael.

Effect of climate change

Michael’s strength may reflect the effect of climate change on storms. The planet has warmed significantly over the past several decades, causing changes in the environment.

Human-caused greenhouse gases in the atmosphere create an energy imbalance, with more than 90% of remaining heat trapped by the gases going into the oceans, according to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association. There’s evidence of higher sea surface temperature and atmospheric moisture, experts say.

While we might not get more storms in a warmer climate, a majority of studies show that those that do form will get stronger and produce more rain. Storm surge is worse now than it was 100 years ago, thanks to sea level rise.

According to Climate Central, a scientific research organization, the coming decades are expected to bring hurricanes that intensify more rapidly, should there be no change in the rate of greenhouse gas emissions.

“Rapid intensification” took Michael from a tropical storm with sustained winds of 40 mph at mid-day Sunday to a Category 1 hurricane with sustained winds of 75 mph by mid-day Monday. It experienced a second bout of intensification on Tuesday, going from a 100 mph Category 2 to a dangerous Category 4 storm with 145 mph winds by Wednesday morning.